Hearing with light, seeing with sound

| 23 May 2015Improvement to tissue-imaging technique based on photoacoustic spectroscopy shows promise for minimally invasive radiology

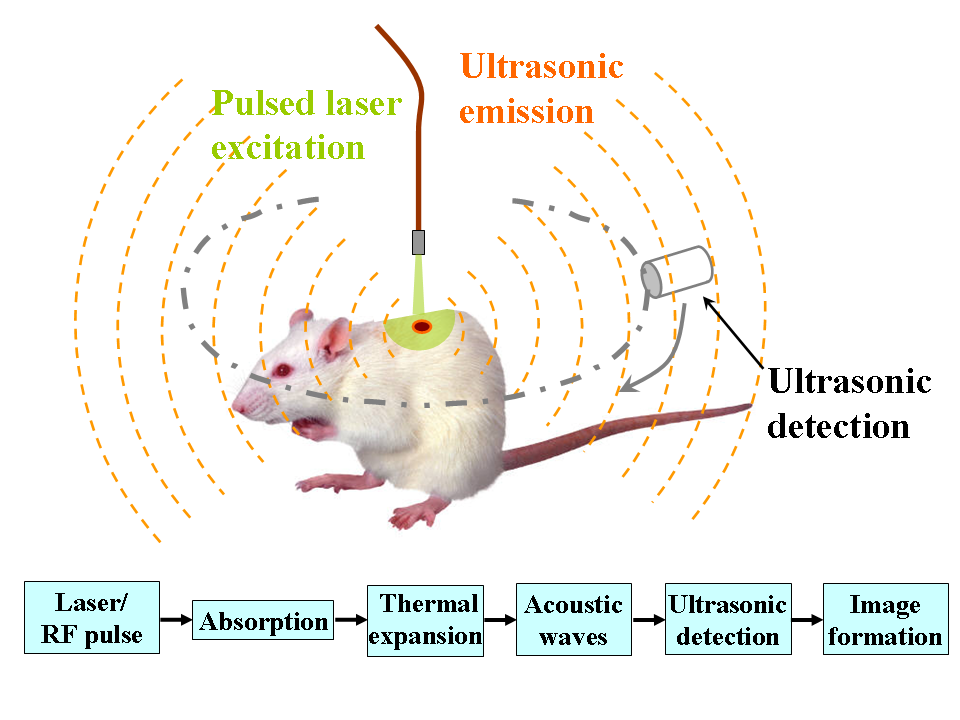

Photoacoustics (PA) involves shining light (photo–) on a material to produce sound (acoustics) and using the sound for spectroscopy1. When energy from the incident light is absorbed by a material it expands slightly and when the light source is switched off the material contracts. Alternately shining and switching off the light source rapidly creates pressure differences that manifest as sound waves. Materials will vary in the sounds they produce depending on the wavelength of light shone on them. A light-vs-sound spectrum for a particular material can be prepared by “listening” to the pressure waves that various wavelengths of light make in it, allowing one to see with sound. The photoacoustic effect was discovered by Alexander Graham Bell in the late 19th century, but has found use in materials science and medicine relatively recently.

Schematic illustration of photoacoustic imaging. Image by Bme591wikiproject / CC BY-SA 3.0

PA imaging provides a guiding mechanism for medical procedures without the risks of ionising radiation and the cost of expensive equipment. Light from lasers is shone on photoabsorbers, such as haemoglobin; the resulting sound waves are detected by transducers and translated into visual images of the targeted region. PA also provides high-contrast images of the surgical tools being used in the medical procedure.

This imaging technique has, however, come with a severe limitation so far: the deeper the light goes into tissue, the less photo-energy per unit area can be delivered, reducing the resolution and constraining PA imaging’s penetration depth. Since the energy of the laser cannot be arbitrarily increased to probe even deeper into tissue — these matters being regulated by bodies such as the American National Standards Institute — a new approach has recently been explored. In laboratory (non-clinical) conditions, researchers modified their surgical apparatus so that a fiber-optic light source could be inserted along with it into the material under observation, allowing the light to be shone not from the surface but from within the material (i.e. it is irradiated interstitially). The transducers, responsible for picking up the sound waves, continued to be located externally. Tests were carried out on a laboratory surrogate for tissue known as a tissue-mimicking phantom as well as prostate tissue from pigs and liver tissue from cows.

The researchers found that the use of an interstitial light source improved the penetration depth of the imaging technique well beyond previously established limits. Wires inserted into the tissue surrogate at depths of 7, 20, 37 and 47 mm were clearly visible using the novel method, whereas the conventional method only showed the wires at the two shallower depths. The tests on the prostate and liver tissue proved to be similarly successful. Shining light from within, the researchers demonstrated, was key to significantly expanding how deep within tissue PA imaging can be employed.

Despite the successes of the laboratory studies and the fact that the size of the fiber-optic cables needed is compatible with the surgical instruments currently used, the outlook remains conservative. For example, the researchers noted that the energy absorbed per unit area in the region immediately surrounding the interstitial fiber-optic laser may be a concern, but suggested that this could be mitigated by increasing the diameter of the fiber end-cap or by adding a diffuser around its tip.

Citation:

Mitcham, T., Dextraze, K., Taghavi, H. Melancon, M., & Bouchard, R. (2015). Photoacoustic imaging driven by an interstitial irradiation source. Photoacoustics, 3(2), 45-54. DOI: 10.1016/j.pacs.2015.02.002

-

An overview of the phenomenon can be found at spectroscopyonline.com/photoacoustic-spectroscopy. ↩