Prism break, cuttlefish style

| 16 May 2015A suggested biological color vision mechanism exploits optics

From humans to mantis shrimp, the key to seeing in color is to compare. With at least two different types of wavelength-sensitive cells in the eye, you can start to distinguish different parts of the spectrum, and thus different-colored objects in the environment. The more photoreceptor types you have, the more precisely you can interpret the incoming light, depending on how finely or evenly the photoreceptor sensitivities are spaced on the spectrum. Humans are trichromatic, with three kinds of cone cells well-tuned to the short, medium, and long wavelengths of our diurnal environment. The mantis shrimp has 16 photoreceptor types, suited to both its vibrant patchwork body coloring as well as its bright surroundings. The question then is, how many photoreceptors does the cuttlefish, a squid-like underwater chameleon, have?

Alas, the cuttlefish has but one type of photoreceptor. The instantaneous color and texture changes exhibited by this mollusk allow it to blend in seamlessly with any background it encounters, but it is effectively color blind, at least if color vision depends on comparison between cell types. Some new research, however, suggests that “color blind” cephalopods like the cuttlefish can sense chromatic information using an optical trick.

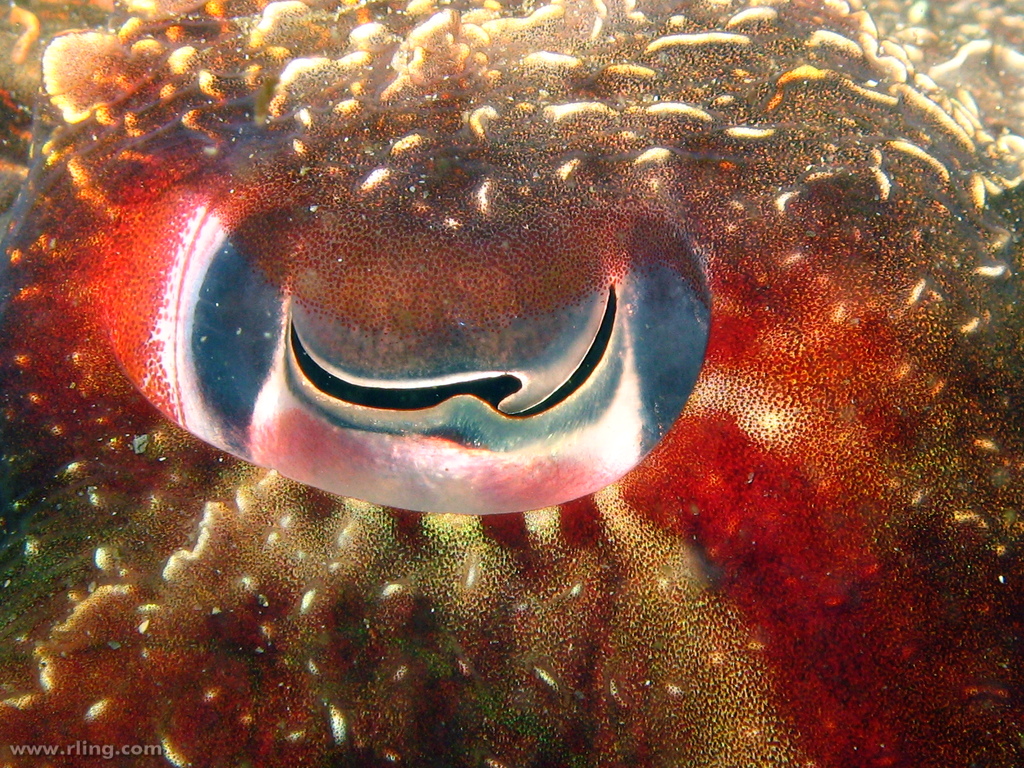

Eye of Australian giant cuttlefish (Sepia apama). Photo by Richard Ling / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Cuttlefish eyes make use of some interesting properties of light. Specifically, their pupils are unusual W-shaped slits that amplify chromatic aberration, or the way light of different wavelengths bends slightly differently. Chromatic aberration explains purplish fringes sometimes seen in photographs: short wavelengths (blue light) get refracted or bent more than long wavelengths (red light)1. Eliminating these “errors” is hard in any optical system, whether it’s eyes or cameras. For the cuttlefish, this aberration signal actually provides valuable color information that is undetectable with only a single photoreceptor type.

Unlike the round human pupil, the squiggly pupil of the cuttlefish lets in light peripherally, off of the optical axis. This means the chromatic effects – how differently the incoming wavelengths are focused – are enhanced. Through its normal accommodation (focusing), the cuttlefish can infer the colors of the environment, effectively using the distance it needs to focus as a clue to color.

For this system to work, the environment of the cuttlefish has to be full of cues to help it accommodate, like shadows and texture. Moreover, these features have be fairly sharply segregated spectrally (that is, neighboring objects need to be different and non-overlapping in hue), and fortunately for the cuttlefish they are. With its ersatz color vision mechanism the cuttlefish can’t distinguish a broad flat field of a single color, though.

Through computer simulations with different spectral inputs and pupil shapes, the researchers conclude that color information is in principle available to the cuttlefish. This may be the elusive mechanism to explain how cuttlefish make the spectral discriminations that are compatible with their vivid displays and camouflage abilities. New kinds of color vision tests, ones that don’t presuppose opponency or comparison mechanisms, are needed to experimentally determine the color sensitivity of cuttlefish vision; according to the simulations, the cuttlefish eye can distinguish colors unambiguously, as long as objects are at least 0.75 meters away. This kind of analysis also raises the question of how other species with annular pupils, such as certain dolphins, might make use of the cuttlefish’s optical trick for color discrimination.

Playing off sensitivity in one domain (color) against another (focal length) is a deft adaptation to compensate for apparent sensory deficits. Studying these adaptations, for example the diversity of pupil shapes in nature, demonstrates that the eye has evolved to be exquisitely tuned to its surroundings.

Citation:

Stubbs, A. L., & Stubbs, C. W. (2015). A Novel Mechanism for Color Vision: Pupil Shape and Chromatic Aberration Can Provide Spectral Discrimination for “Color Blind” Organisms. bioRxiv, 017756. DOI: 10.1101/017756

-

Light isn’t colored but we colloquially refer to long wavelengths of the visible spectrum as red and short wavelengths as blue. ↩